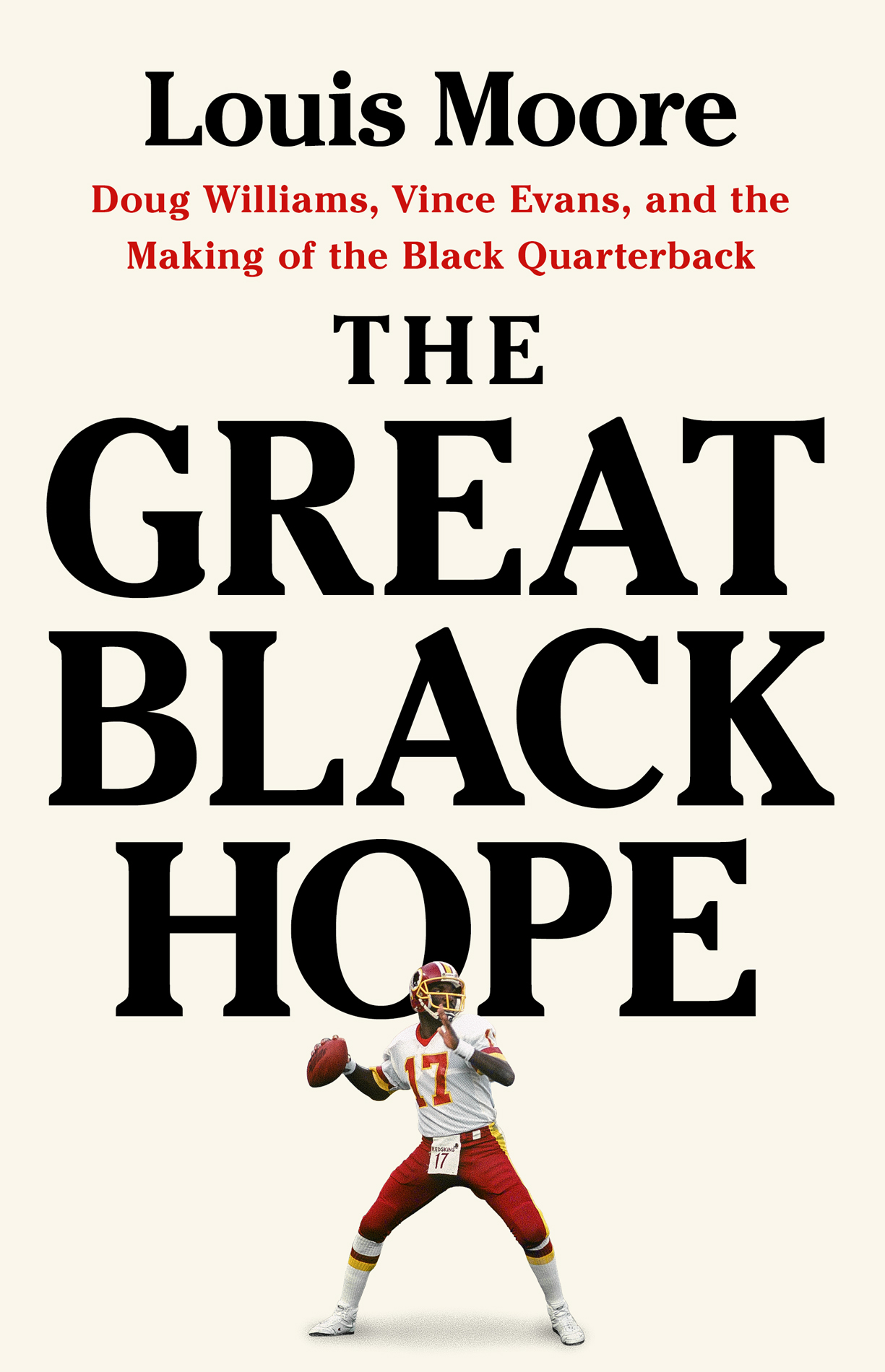

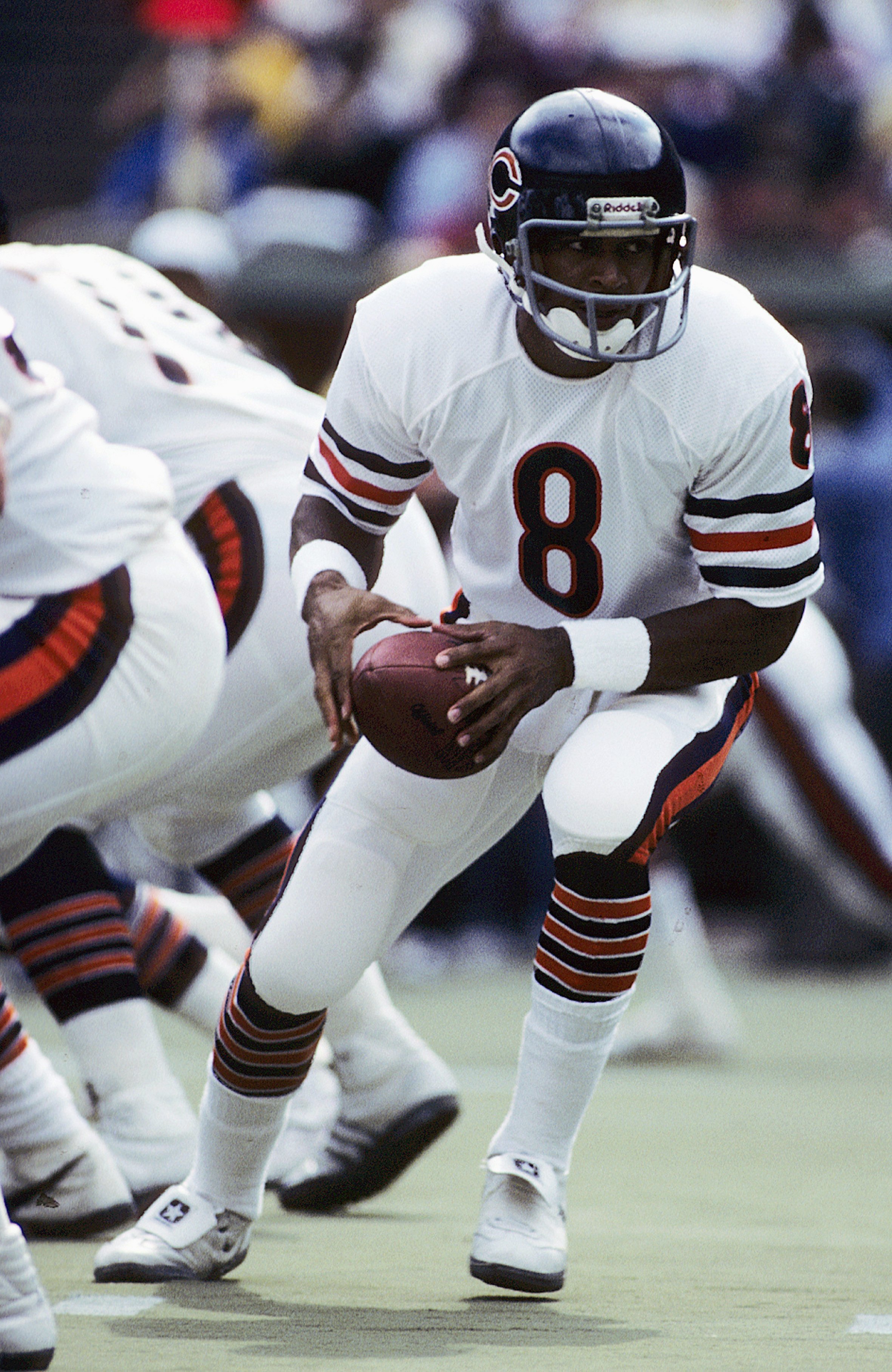

Chicago’s Soldier Field hosted a stylistic clash of groundbreaking quarterbacks on Sept. 30, 1979. Big-armed Doug Williams, a classic dropback thrower, helmed the visiting, undefeated Buccaneers. The Bears countered with dual threat Vince Evans, whose explosive, 65-yard screen toss to Walter Payton lessened the home team’s margin of defeat.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/NAIjPNhJX5I?si=VnA6JHKQVnCOmbEH&start=934

A parallel between the passers made the game historic. Their matchup, the NFL’s first between Black starting QBs, helped dispel the prejudice that players who looked like them couldn’t be counted on to dissect a defense or lead.

Williams and Evans were born during the same summer in the segregated American South at the outset of the civil rights movement. They weathered racist taunts, personal loss, and benchings to briefly dazzle under center and create chances for younger peers to flourish.

Their paths eventually split: Williams was MVP of Super Bowl XXII in 1988 – Washington, his second team, pounded the Broncos 42-10 – while Evans became a backup with the Raiders.

Their breakthroughs changed quarterbacking – almost half of NFL teams now field a Black starter – and inspired a new book, entitled “The Great Black Hope,” by the race and sports scholar Louis Moore. He’s a Grand Valley State University professor who studies how Black athletes shaped American history.

“So much of the struggle of the Black American was wondering whether promise would come to fruition: ‘Am I really going to get an opportunity, or is my color going to continue to hold me back?'” Moore said.

“For Black fans (in the 1970s and ’80s), the quarterback is the most important position in all of sports. It signals to them that guys will actually get a chance. If Doug and Vince make it – or, later, if Randall Cunningham or Warren Moon is going to make it – then I’m going to get a chance, too.”

Before Moore’s book launched this week, the author spoke to theScore about Williams and Evans’ triumphs, tribulations, NFL legacies, and resemblance to two active stars. The conversation’s been edited for length and clarity.

theScore: Fans know about Williams’ historic Super Bowl triumph. Evans didn’t realize his potential, but you wrote that in his first few seasons, he represented the future of football. How so?

Moore: It’s the idea that you can have a true dual-threat quarterback – not a scrambler, but a guy who can have an offense built around his passing and running skills. The Bears were the first team to think about that. In 1980 (Evans’ fourth NFL season), he does great as a backup, and he gets the starting role in ’81.

Those are the years when they’re the first organization to say: “You know what? We have this Corvette. Are we going to test-drive it or keep it parked in the garage?”

It doesn’t go so well, because I think there’s no blueprint for them. The college game is not the same as the pro game. The college game is the wishbone and triple options.

Vince struggled because he was never a classic quarterback. But it sets the tone for things to come. A few years later, you’re going to get Cunningham. You’re going to get Steve McNair, Michael Vick, and Daunte Culpepper. You’ll get Colin Kaepernick. Lamar Jackson. Jalen Hurts. All the guys today.

Vince, to me, is that prototype. It just doesn’t work out in real time.

In the 1950s and ’60s, Black college QBs invariably got moved to receiver or cornerback in the NFL because of racial stereotypes. Teams thought they were fast but not brainy. They were seen as athletes but not leaders. What had changed by the time Williams and Evans turned pro?

Williams is drafted in ’78. Evans in ’77. Nothing’s changed. It’s just that they were so good that it was hard to pass up.

Williams ended his college career as the most prolific passer ever. How do you pass that up? The other thing that helped him was playing a few games against white teams. People see this. There’s a Heisman run for him. It was clear that he was the best in college.

Evans is playing on TV for USC in the Rose Bowl, and he’s pretty good. There were two organizations that were willing to take a chance on them.

Sept. 30, 1979: What did their head-to-head matchup in Chicago symbolize?

It’s the modern NFL. (On a recent Sunday), we had three games where Black quarterbacks went head-to-head. That’s normal now, whereas at that time, it was the first instance in modern football. You start to see the shift.

A decade before, it was unthinkable. There was one starting Black quarterback: James Harris for the Bills in 1969. It doesn’t happen right away after the ’79 season, but this is what the NFL came to look like, because these guys were electrifying, they could move, and the fans were starting to be receptive.

Williams helped an awful Buccaneers expansion team quickly become a playoff contender. Evans showed flashes of brilliance in middling Bears offenses. How were they treated by those fan bases?

For Doug, it was up and down. In 1970s America, the South is still coming to terms with integration. There’s hate mail. His coach was called an “N-word lover.”

Black fans always supported him. That’s a given. You also see how big of a star he was. He was the biggest drawing card in 1978. Fans would unfold signs that say, “Doug’s cool.”

But when things went bad, they really went bad. He was never judged on being a quarterback. He was judged on being a Black quarterback. What that meant in the 1970s and ’80s, you can’t detach that from race and racism.

There was more fan support early on for Vince because he was a backup. I don’t care what your color is – American fans love backup quarterbacks when the starter’s awful, and the Bears had awful quarterbacks. As long as Vince was on the bench, they loved him. They thought he was fast, exciting, and electrifying. You see that in his first few games that he started where he’s dropping 50-yard bombs for touchdowns.

The problem comes when you struggle. That’s when they turn on you. The alternative for him wasn’t necessarily the white guys who weren’t good, but by the time you get to ’82, rookie Jim McMahon. His time was pretty much over once that happened.

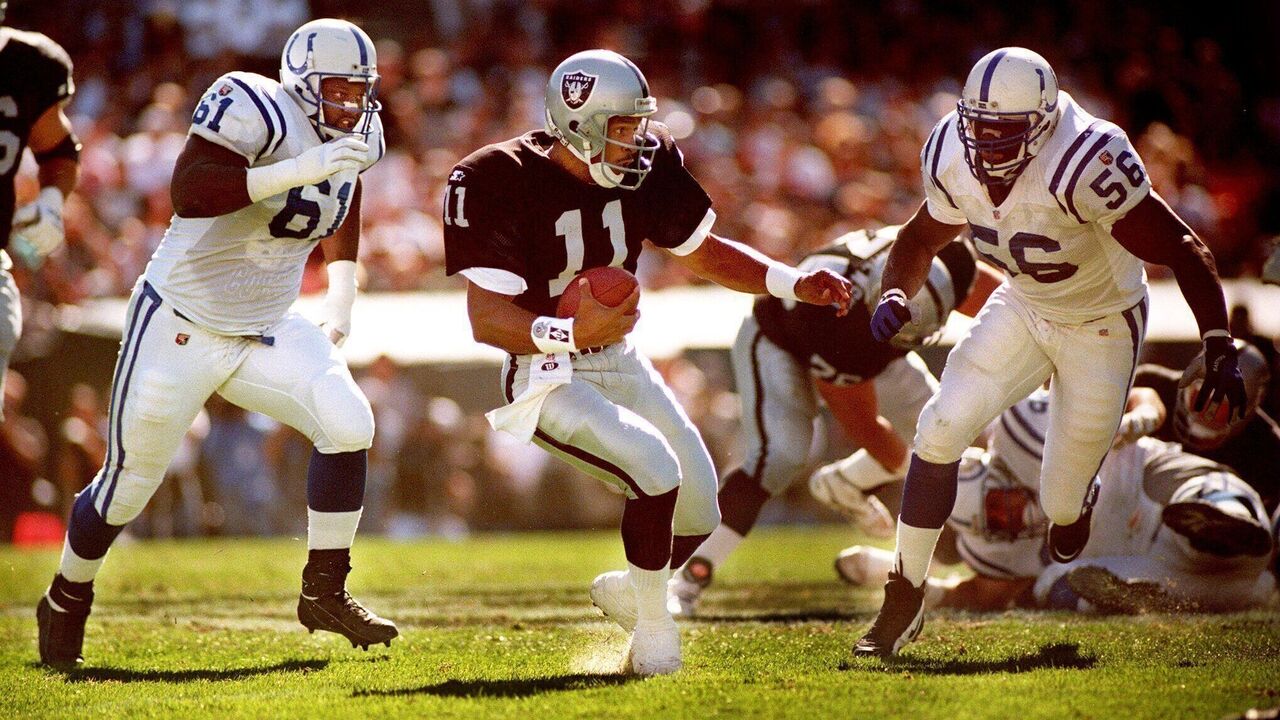

Following stints in the USFL, returning to the NFL defined Williams and Evans as players. Doug got his crowning moment in the Super Bowl. Vince scuffled to become the Raiders’ longtime backup. What adversity did they overcome and how did they exhibit resilience on the path to achieving those things?

For Doug, there’s the well-known stuff: He’d just married, had a baby, and he loses his wife in 1983 while trying to negotiate a contract. When he goes onto the USFL, he struggles a bit, and then the NFL doesn’t call him. Luckily, Joe Gibbs, his coach in Washington, was his offensive coordinator for a year at Tampa Bay. He remembers him and brings him on.

In the ’86 season, he barely plays. That ’87 season leading into the Super Bowl is up and down. He loses his starting job. It’s rare that we see football players cry in press conferences, but he’s crying. It’s taken away from him, and all that he’s been through – all the racism that he had to fight being a Black quarterback – is coming to his mind, and he can’t control those emotions.

But (replacement QB) Jay Schroeder’s not that good, and so at the end of the season, they put (Williams) in. He wins the last game of the season, and his coach is like: “We’re going to ride with you.” And the rest is history – for that year. The next year, he struggles and gets hurt, and he’s gone (from the NFL) within two years.

Now, Vince, different story. Nobody wanted a piece of Vince Evans. The NFL was done with him, and then the strike came in 1987. Like a number of Black quarterbacks in the strikes of 1974 and ’87, Vince took an opportunity and crossed the picket line. His teammates see him as a scab, but the Raiders and Al Davis like him. Al’s a pretty open-minded guy. He was the first owner to sign a Black head coach in Art Shell.

Vince makes it with the Raiders and, for the next eight years, on again and off again, gets cuts only to be brought back. That makes him the first career Black backup. There’s no role for a Black backup quarterback at that time. You’re either starting, out of the league, or at another position.

The fact they let Vince stay on made room for guys today like Josh Johnson, who’s probably in his 15th year as a career backup. Tyrod Taylor: career backup. Charlie Batch before them. Guys who are there just in case there’s an emergency. That’s who Vince Evans became.

A key person in the book is Eddie Robinson, the legendary Grambling coach. Sending Black quarterbacks to the NFL was a mission for Robinson. His sophisticated, pro-style dropback offense helped Williams become an attractive prospect. What did his role signify about the importance of coaching?

One thing he didn’t have to deal with was all the pushback, because he was at a Black school. But the fact you can build a system around a Black quarterback – nobody thought you could do that. Robinson proved that you can time and time again.

He served as this mentor for guys like James Harris and Doug Williams. He urged them to stay the course, and never to complain. My guess is, in real time, Doug Williams and James Harris wanted to lash out in the face of racism. Because Robinson taught them to keep their cool and keep pushing ahead so the next guy has an opportunity to come up behind them, that’s what you get.

You mentioned Harris, the first Black full-time NFL starter. He mentored Evans and Williams when they were in college. All three in retirement started a group called the Field Generals to support younger Black QBs. What lessons and wisdom have been passed between generations?

What Harris did was essential. There were only a handful of QBs at that time who’d ever experienced what they did. Harris was the older guy who could talk to them.

You think about the guys who didn’t get it. They struggled. Marlin Briscoe, who was the first one to start (a handful of games) in 1968, wound up having a drug problem a decade later. Joe Gilliam, who started in ’74 for six games, wound up having a drug problem.

Mentorship was huge to these guys. They realized moving forward, “We’ve gone through a lot of stuff.” They could be there for others to make sure they can handle a blitz, and they can also handle the fans, GMs, and coaches.

When you watch the NFL, which QBs make you think of Williams, and who reminds you of Evans?

The best case is Super Bowl LVII (between the Chiefs and Eagles). You’ve got Patrick Mahomes and Jalen Hurts.

Hurts and Evans were very similar. They’re short, they’re compact, and they’re fast with powerful arms. They’re still trying to figure out precision passing.

Williams and Mahomes are talented pocket quarterbacks, can move, and can make any throw. That’s why they called Doug Williams the Rifleman. He’s a gunslinger just like Mahomes. To me, it’s the perfect comparison.

Nowadays, Black QBs win MVP awards and championships. They headline the top of the draft. What will their accomplishments mean in the future?

The future’s Black. We’re not even thinking about it anymore. Doug Williams wasn’t a “Black quarterback” until he gets into this white space. The more we move on, it’s going to be a Black position. The way the guys are playing today, it’s a copycat league, and it’s going to make it easier for the next guy.

A great example is the past two drafts. Back-to-back first and second picks are Black quarterbacks. Last year, it was Bryce Young, C.J. Stroud, and then the fourth pick is Anthony Richardson. This year, it’s Caleb Williams, it’s Jayden Daniels, and Michael Penix Jr. goes early in the first round. Next year, probably Shedeur Sanders if he gets his stuff together. It’s becoming the norm of what we see.